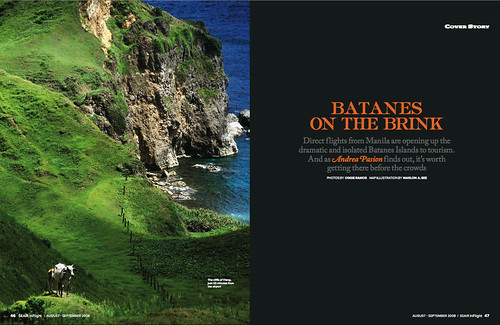

Direct flights from Manila are opening up the dramatic and isolated batanes islands to tourism. and as Andrea Pasion finds out, it’s worth getting there before the crowds.

Direct flights from Manila are opening up the dramatic and isolated batanes islands to tourism. and as Andrea Pasion finds out, it’s worth getting there before the crowds. Batanes is unlike any other place in the country, a wild smattering of islands in the north where cliffs meet the sea on pebbled shorelines and goats and cows are sent out to pasture among green hills. These islands have been described as looking more like the Scottish Highlands than the Philippines. There are no swanky hotels, no chic restaurants and often there’s not even electricity. The food is freshy not fancy, and evening entertainment consists of identifying the constellations in the heavens over a cold bottle or two of San Miguel Beer.

The Batanes islands – some of which are closer to Taiwan than the Philippines – are so remote that it’s easy from Manila to forget they even exist. direct flights to the town of Basco have made the islands reasonably accessible from the capital, but they still retain a quality of isolated otherworldliness that makes them feel like the island that time forgot.

The province is often hit by typhoons that blow in from the east during the rainy season. In the dry season, it’s hot and sunny, but not as blisteringly hot as Manila or the Philippines’ mainland.A s the plane sweeps in to land you get a glimpse of the drama below: waves crashing on rock, a cow perched precariously on a cliff’s edge, the runway sloping upwards towards the flanks of volcanic Mt. Iraya.

This is a step back into a simpler world. While we were there, electricity was rationed because two of Batan island’s three power sources were waiting for spare parts from Canada. If one part of the town had lights in the evening, it meant another part was in darkness. The schedules would be switched the following day to accommodate those who had missed out the day before.

We could not have come at a better time, nor could the blackouts have happened at a more inopportune moment. This was Batanes Day, June 26, a holiday that’s actually celebrated for a whole month, with classes suspended for a week. There were daily games, parades and a trade fair at the little plaza in Basco, the capital. Every morning trucks transported people into the town center for softball, volleyball and relays, and trucked them out in the afternoon when the day’s events were done. the islanders were in a celebratory mood.

At Shanedel’s, the homey little pension in Basco where we stayed, at least there was a generator, one of the few places in town that had one. It meant guests were assured of lights for three hours of the evening. Without air-conditioning, it was sometimes sticky and hot, but the warm welcome at Shanedel’s made-up for occasional moments of lost sleep because of the heat.

At Shanedel’s, the homey little pension in Basco where we stayed, at least there was a generator, one of the few places in town that had one. It meant guests were assured of lights for three hours of the evening. Without air-conditioning, it was sometimes sticky and hot, but the warm welcome at Shanedel’s made-up for occasional moments of lost sleep because of the heat.Over breakfast of dried flying fish, Shanedel’s owner Dely Millian showed me three magazines where the inn has been featured: one of them had a picture of actor Richard Gomez holding a huge yellow fin tuna. I was reminded of the movie he made here with actress Dawn Zulueta, Hihintayin Kita sa Langit which in English means "I will wait for you in heaven," the first film shot in this location.

On day one, we zipped around Batan in a van with sliding doors kept open to the air in; the van’s air-con was not working either because it needed a spare part that wasn’t available on the islands. Almost everything here has to be shipped or planed in from somewhere else, so waiting is a fact of life.

We traveled through the hills of Vayang, Naidi and an area known as “Marlboro Country” because of its cattle and horses. At Valugan we explored a boulder beach and ancient windmills.

Our guide was Mang Romy, who took us to Loran station, the lighthouse that formed a dramatic backdrop for the movie Hihintayin Kita sa Langit. Romy told us this was where the Filipino version of Wuthering Heights was shot.

In Songsong, a barrio at the southern part of Batan island, he pointed to the Ivatan limestone house where actress Iza Calzado stayed ruing the filming of the movie "Batanes". Well, what makes the house special now’s plain and simple: Calzado made it her home during the duration of the shoot.

There are more stone houses to be seen at the UNESCO-nominated heritage site in Barangay Savidug and Chavayan, both on Sabtang island, less than an hour’s trip by boat from Batan.

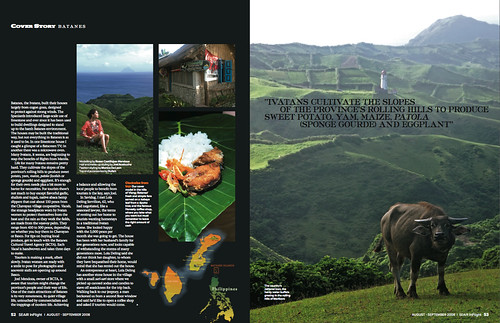

There are more stone houses to be seen at the UNESCO-nominated heritage site in Barangay Savidug and Chavayan, both on Sabtang island, less than an hour’s trip by boat from Batan.Before the spaniards arrived in the Philippines, the indigenous people of Batanes, the Ivatans, built their houses largely from cogon grass, designed to protect against strong winds. The Spaniards introduced large-scale use of limestone and ever since it has been used to build dwellings designed to stand up to the harsh Batanes environment. The houses may be built the traditional way, but not everything in Batanes is as it used to be. In one limestone house i caught a glimpse of a flatscreen TV; in another there was a microwave oven. Many Ivatans, it seems, are beginning to reap the benefits of flights from Manila.

Life for many Ivatans remains pretty hard. They cultivate the slopes of the province’s rolling hills to produce sweet potato, yam, maize, patola (loofah or spong gourde) and eggplant. It’s enough for their own needs plus a bit more to barter for necessitites. For tourists, there’s not much to buy except flavorful garlic, shallots and tupak, native abaca hemp slippers that cost about 150 pesos from the Chavayan village cooperative. Vaculs, the strange headpieces worn by Ivatan women to protect themselves from the heat and the rain as they work the fields, are made from the voyavoy palm. They range from 450 to 500 pesos, depending on whether you buy them in Chavayan or Basco. For tips on buying local produce, get in touch with the Batanes Cultural Travel Agency (BCTA). Each Vacul is handwoven and takes three days to make.

Tourism is making a mark, albeit slowly. Ivatan women are ready with a smile to pose for photographs and souvenir stalls are opening up around Basco.

Joel Mendoza, owner of BCTA, is aware that tourism might change the province’s people and their way of life. One of the main attractions of Batanes is its very remoteness, its quiet village life, untouched by commercialism and the trappings of modern life. Achieving a balance and allowing the local people to benefit from tourism is the key, says Joel.

Joel Mendoza, owner of BCTA, is aware that tourism might change the province’s people and their way of life. One of the main attractions of Batanes is its very remoteness, its quiet village life, untouched by commercialism and the trappings of modern life. Achieving a balance and allowing the local people to benefit from tourism is the key, says Joel.In Savidug, I met Lola Deling Servillon, 62, who had negotiated like a seasoned lawyer, the terms of renting out her home to tourists wanting homestays in a traditional Ivatan home. She looked happy with the 3,000 pesos per month she was going to get. The house has been with her husband’s family for five generations now, and looks capable of withstanding the storms of many generations more. Lola Deling said she did not think her daughter, to whom they have bequeathed their home, would mind that she has rented out the house.

An entrepreneur at heart, Lola Deling has another stone house in the village with a small sari-sari store where we picked up canned sodas and candies to stave off seasickness for the trip back.W alking back to our jeepney, a man beckoned us from a second floor window and said he’d like to open a coffee shop and asked if tourists would come.

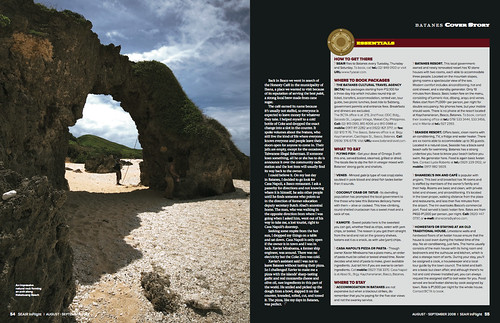

Back in Basco we went in search of the Honesty Café in the municipality of Ivana, a place we wanted to visit because of its reputation of serving the best palek, a strong local brew made from cane sugar.

The café earned its name because it’s usually not staffed, so everyone is expected to leave money for whatever they take. I helped myself to a cold bottle of Coke and dropped the exact change into a slot in the counter. It spoke volumes about the Ivatans, who still live the kind of life where everyone knows everyone and people leave their doors open for anyone to come in. Their jails are empty, except for the occasional Taiwanese illegal fisherman. If someone loses something, all he or she has to do is announce it over the community radio station and the lost item will usually find its way back to the owner.

I could believe it. On my last day in Batanes, I decided to go look for Casa Napoli, a Basco restaurant. I ask a passerby for directions and not knowing where it is himself, he asks other people until he finds someone who points us in the direction of former Education Deputy Secretary Butch Abad’s ancestral home. The man, who was walking in the opposite direction from where I was going when i asked him, went out of his way to take me, a lost tourist, right to Casa Napoli’s doorstep.

I could believe it. On my last day in Batanes, I decided to go look for Casa Napoli, a Basco restaurant. I ask a passerby for directions and not knowing where it is himself, he asks other people until he finds someone who points us in the direction of former Education Deputy Secretary Butch Abad’s ancestral home. The man, who was walking in the opposite direction from where I was going when i asked him, went out of his way to take me, a lost tourist, right to Casa Napoli’s doorstep.Seeking some respite from the hot sun, I dropped my things on a table and sat down. Casa Napoli is only open if the owner is in town and I was in luck. Xavier Mirabuena, a former ship engineer, was around.T here was no electricity but the Coke Zero was cold.

Xavier’s assistant said i was not to leave Batanes without tasting their pizza. So I challenged Xavier to make me a pizza with the island’s sharp-tasting garlic and real mozzarella cheese and olive oil, rare ingredients in this part of the world. He smiled and picked up the dough from a bowl, slapped it on the counter, kneaded, rolled, cut, and tossed it. The pizza, like my days in Batanes, was perfect. (lifted en toto from the Seair InFlight Magazine cover feature, Aug-Sep 08 issue, Text by Andrea Pasion, Photography by Oggie Ramos)