"We are born into a world of rectangular boxes, perfumed air, our nights lit by bulbs of white glass, our days quantified by the ticking circles we strap to our wrists."

Eric Pinder,

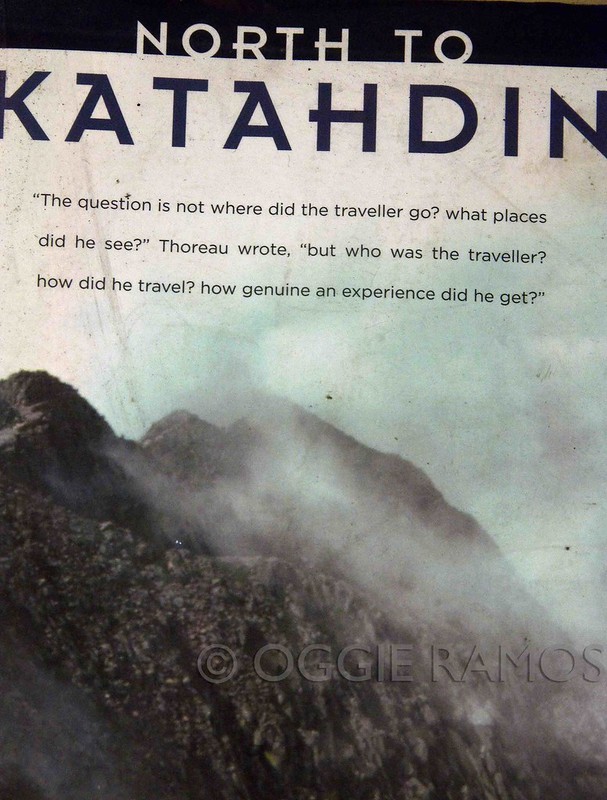

North to Katahdin

Millinocket, Maine is over 5,000 miles away from where I sit but reading the vivid details of Eric Pinder's inspired writing in "North to Katahdin" made the mountain very real to me as if I've wandered the oft fog-draped mountain myself.

Eric writes with a natural fluidity befitting his interest and topic, an exploration of the lay of Katahdin as well as the landscape of Henry David Thoreau's mind who've explored and wrote about the mountain and about nature. An almost mile-high mountain, Katahdin is the conclusion of the 2,160 mile-long Appalachian Trail and to those in Maine, the closest they have to a wilderness.

Eric undertakes the journey with much introspection, bereft of chest-thumping and breast-beating as he confesses of suffering from sore knees and damp clothing while examining the reasons why we climb mountains beyond the perfunctory, almost-cliche'd answer of "because it's there."

Eric's mindful meanderings tackle a lot of things I myself often think about that several times during the course of reading, it feels like the author is a kindred spirit and that he was looking into my head and pulling the thoughts out of it.

Wilderness has become a fetish for people dissatisfied with the smog of cities. It's supposed be somehow purer than we cifified, civilized humans are, eagerly sought by those in need fo spiritual healing -- though some would argue that humans, too, are a part of the natural world. We belong to the wilderness, they say, not the other way around. Our guile in harming the environment makes us try to exclude ourselves from it. This is a mistake. If we define wilderness as the complete absence of people, then there is no wilderness left...

I've often thought of this as I took up hiking after decades of living in the city. What's out there that begs for torturing yourself walking for hours on end. Perhaps for an hour or so of fleeting solitude? Of escape from the encumbrances of the city, to which Eric writes "Don't people realize that they cannot escape the city if the whole metropolis moves with them?"

I've also often pondered on what can be done from a conservationist's point of view and Eric offers a pragmatic remark, "The philosophy of conservation is exactly what its detractors accuse it of being: selfish. The problem facing conservationists is that they can never be a majority. They must fight against a growing population that wants electricity, water, newspapers, jobs, and places to live." If only Teddy Roosevelt were alive today, he would probably reiterate his point to "Leave (nature) as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it."

Not even 200 pages, the book deserves a slow read, and re-reading, with anecdotes and observations that make me see nature in a new light -- of finding a thousand suns in the twinkle of the lake waters, of seeing the gibbous moon change colors before falling down to the hills, of hearing the murmur of brooks, of sensing the mischief of a swirling wind. So why climb a mountain? Perhaps, Eric and Henry David Thoreau offer some answers.

"There are certain things we go to mountains to find: sun, moon, sky. We seek the mountains to lift our spirits, to stand a a little closer to the stars. The question is not where did the traveller go? what places did he see?" Thoreau wrote, "but who was the traveller? how did he travel? how genuine an experience did he get?"

Attributions: North to Katahdin, 2001 Eric Pinder, Published by Milkweed Editions, ISBN-10:I-57131-280-3