|

| Wall of memories |

Choosing to wake up well after sunrise is a luxury savored well after the generator goes off at 5:30am. We didn't have time to make arrangements for transportation to get to a good sunrise vantage point the night prior anyway. But book a guide to the island's interior down south we did, scheduled for the afternoon. That meant we had the morning free to see a bit more of the town. Should be the museum, for no guest should leave Culion without seeing it and knowing its significance.

|

| Bright and airy inside with light-colored walls that speak of health and healing |

It wasn't open but Mauricio, the friendly caretaker, unlocked the doors for us as well as switched on the lights and ventilation in the particular areas where we are, switching them off when we leave (speaks volume on how valuable electricity is in the islands). The walls have a fresh-looking coat of light-colored paint (barely a year old, Mauricio tells us) which gave the museum an airy and light feeling, perhaps conveying the message that yes, leprosy once was widespread on the island but has now been vanquished and relegated into the history books.

|

| Installations and pictures conjure images of life back then |

Ricky further points out that "a majority of the present-day inhabitants of the island... can directly trace their lineage to former patients, if are not former patients themselves. Others link their roots to the pioneer doctors, nurses, staff or administrators of the former leprosarium." (A longtime friend, I will later found out, was the grandson of the colony's Chief from 1920-25, Dr. Jose Basa Avellana; his mother was in fact born in Culion).

|

| Photographs and memories of healing |

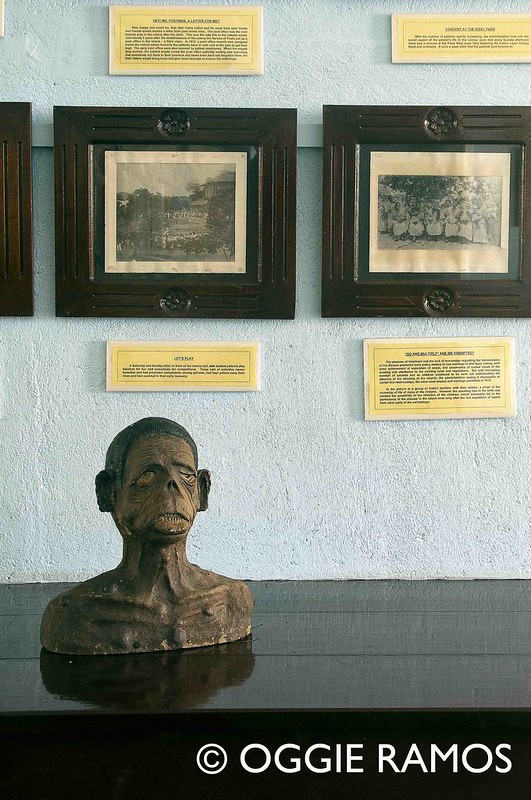

Upon reaching the landing at the top of the stairs, one cannot help but notice the bust of an actual patient, his face disfigured by the malady. We were quite taken aback when our guide, Hermie, told us later that he knew the man and up to now, can imagine him speaking whenever he sees the bust. On the second level, there's a room with an assortment of equipment -- wall-mounted telephones, huge dentist chairs, and a multitude of stuff from a bygone era. Apart from the visual records, there are written records that reveal so much of what transpired here. Curious that in the individual records, "patients were referred to as 'inmate', and any subsequent release from the facility was termed a 'pardon'," perhaps owing to the literal criminalization of leprosy at the time under The Segregation Law of 1907 passed by the colonial government.

|

| "Curiosities" room on the second floor |

A cure has been found decades ago and the island is no longer a segregation place but rather, a municipality of second and third generation descendants. However, I guess the stigma persists as Ricky writes, "In Philippine contemporary memory, Culion still connotes affliction and banishment to an 'island of no return.' It also gained a more sinister reputation as an 'island of the living dead.' " Not surprising why eager tourists flock to Puerto Princesa, El Nido or Coron but totally skip Culion or just make a brief stopover.

The importance of the museum goes beyond the superficial reason of just having one. The museum and its archives are part and parcel of the collective memory. The records are proof that "not all patients in Culion were brought there to die; many lived almost normal lives, got married, had children, and were productive citizens who contributed to the development of the community." Ricky Punzalan further writes, "the Culion Leper Colony records became the centre of attention for a community seeking for something tangible that could articulate and embody its collective heritage and symbolize its hundred years of existence."

|

| Installation at the first level -- bed with mosquitero |

On the way out, I asked Mauricio what his complete name is. Instead of replying, he pointed to a plaque at the entrance, a commemoration from a Japanese humanitarian foundation that included his name, Mauricio Leal. From what we will gather later, he is the son of a former patient and has been serving in the hospital and the museum for over a decade. Apart from the visual and written records, he is a living link to the past, among the few who are selflessly keeping the memory of this former leper colony alive not to relive the hurt of the past but to heal, to find its way into the future.

|

| The Agila emblem on the hill was created in 1926 by leper patients using coral stones |

References and attributions: Notes and quotes culled from an article by Ricky Punzalan, archivist and curator during the museum's centennial (2005-06). www.rpunzalan.com; Roughguides • Recommended reading: Culion: A Leper Colony's 100 Year Journey Toward Healing authored by Yasmin Arquiza and published by the Culion Foundation, 2003, ISBN-13: 978-9719264309 • Tourism guide Pastor Hermie Villanueva conducts walking tours of Culion town as well as elsewhere on the island; he can be reached via mobile: 0921-3947106

Next on Lagal[og]: Culion: Heading to Kabulihan for the Mangroves, Sunsetting at Lele

Next on Lagal[og]: Culion: Heading to Kabulihan for the Mangroves, Sunsetting at Lele